NL GenWeb

Notre Dame Bay Region - Fogo District

The Slades and Fogo

The information was transcribed by DON BENNETT 2001. While I have endeavored to be as correct as humanly possible, there may be typographical errors.

St. Andrew's Anglican Church, Fogo

|

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN SLADE, MERCHANT OF THIS TOWN WHO DIED THE 9TH OF JANUARY 1847. AGED 28 YEARS

ALSO OF ROBERT STANDLEY SLADE WHO DIED AT FOGO IN THE ISLAND OF NEWFOUNDLAND FEBRUARY THE 21ST 1846 AGED 28 YEARS

ALSO OF ROBERT SLADE MERCHANT AND MAGISTRATE OF THIS TOWN FATHER OF THE ABOVE WHO DIED THE 3RD OF JANUARY 1864 AGED 68 YEARS HIS REMAINS WITH THOSE OF HIS ELDEST SON ARE INTERRED IN THE CHURCH YARD NEAR THIS PLACE |

|

TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN SLADE MERCHANT OF THIS PORT AND OF POOLE, DORSET, ENGLAND THE REPRESENTATIVE OF THIS DISTRICT IN THE GENERAL HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE ON THE 9TH DAY OF JANUARY 1847 IN HIS 29TH YEAR

|

covered with an iron plate. On the plate in raised letters are these words:

|

JOHN HAYTER SLADE 1783

ROBERT STANDLEY SLADE 1846

|

John Hayter Slade was the only son of John Slade, 1719 -1792, a merchant and ship owner of Poole, Dorset who in the mid eighteenth century, built a trading empire in Newfoundland. Starting at Fogo and Notre Dame Bay, he and his successors expanded North to the Coast of Labrador and as far south in Newfoundland as St. Mary’s. The Slade companies were in business for over a hundred years and for most of that time they were the biggest firm in the Newfoundland fish trade.

John Slade was born in 1719, the son of a mason, in Poole, Dorsetshire, England. The Port of Poole was steeped in the tradition of the Newfoundland cod fishery. Poole ships with their crews of West Countrymen and Southern Irishmen had been sailing to the Newfoundland coast every Spring, for two hundred years. Slade became a captain while still in his twenties and made his first voyage to Newfoundland in 1748 as master of the trading vessel "Molly." Within five years he commanded his own vessel and within a few years had set up business as John Slade & Co. at Fogo. A branch was soon opened at Twillingate and later at Battle Harbour Labrador. Many smaller branches were opened: Greenspond in Bonavista Bay, Joe Batt’s Arm, Barr’d Islands, Tilting, Change Islands, Sop’s Arm, White Bay, Nipper’s Harbour, Conche. In Labrador, branches were opened at Venison Island, St. Leonard’s, and St. Francis Harbour.

Slade’s success was due in part to being in the right place at the right time. Before the early eighteenth century the Newfoundland fishery was conducted by English, French and in the early years, Basques and Portuguese Merchants who sent ships to the coast each Spring.

The men fished from the ships or from smaller boats. They salted and dried the fish ashore, loaded the cured fish on the ships, returned to Europe and sold the catch. After the Spanish takeover of Portugal in 1583 and the English defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, England and France shared the Newfoundland fishery with little competition from other countries.

West Country merchants and the British government discouraged permanent settlement in Newfoundland throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The right to settle was finally established by the passage of the Newfoundland Act of 1699. The Act made it legal to settle in Newfoundland but not North of Bonavista on the East coast, or North of Cape Riche on the West coast. Fogo was part of this "French Shore" and was off limits to English settlers. It remained so until the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1783. The 1783 treaty moved the Southern limit of the French Shore on the East coast to Cape St. John . This new boundary reflected the reality of what was happening in Notre Dame Bay. English fishermen had begun settling North of Bonavista after the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713, taking advantage of the weakness of the French in the area. Fogo was being settled by 1728, and Twillingate by 1732. Fogo had twenty-five families in1750. Half a dozen ships were coming from England each year, to fish, doubling the population during the summer months. The total amount of codfish shipped from Fogo during this period was close to two million pounds per year.

As the coast became settled, it became clear that the merchants who would survive would be those who could set up premises in Newfoundland, supply the fishermen and market their fish in Europe. The merchants could make more money trading with the shore fishermen than they could with their own fishing vessels operating from England on a seasonal basis. Fishermen who stayed over had a longer season and could be employed in the sealing, trapping and lumber industries. Life in Newfoundland was not easy for the settlers, but it was much better than life in England at the time. Families living in Newfoundland, while not rich, were self-sufficient. They had small gardens, domestic animals, all the salt and fresh water fish, game, and berries they could use. These resources were free to anyone willing to work.

Small, Newfoundland based merchants started to set up their "rooms" at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Within forty years the ship fishery had disappeared and the whole business was in the hands of the local merchants and the shore-based fishermen. When Slade appeared in 1748 the time was right for someone to take over from the small operators and look at the bigger picture of trading in this new area. Notre Dame Bay and further North had not only cod, but seals, salmon, fur and lumber. There was plenty of timber for boat and ship building. What was needed was someone to develop these resources and organize the marketing of products.

From the beginning Slade brought out workers from England and Ireland, signed them up for various lengths of time, usually two summers and one winter in the case of fishermen, tradesmen, and labourers. Apprentices in the trades or apprentice clerks were signed up for the period of their apprenticeship, typically seven summers and six winters. Some were hired for the summer season only , most ship’s captains went back to England each fall. Over the years more of Slade’s servants began staying in Newfoundland and bringing their families. By 1850 almost all employees were recruited locally.

Slade introduced a system of trading that became known as the truck system. He was probably not the first to use this method but he was certainly one of the most successful at it. Under this system of trading, the merchant, Slade in this case, supplied everything his clients needed to survive: food, clothing, building materials, tools, rope, traps, guns and ammunition, prayer books, rum, tobacco, etcetera. He had no competition. At the other end of the scale the merchant bought everything the planter, trapper, logger or salmon fisherman produced, dried cod, cod liver oil, train oil, seal pelts, furs, smoked and salted salmon, berries, lumber.

During the season, employees of the planters and independent operators needed to be paid. This was accomplished by the merchant advancing credit to them, and charging the advances to the accounts of their employers. In the case of Slade Co. employees, each had an account in the ledger and anything the employee bought was deducted from wages due. An entry in the ledger for 1792 shows one, James Warne, who after spending eight years fishing in Newfoundland, had just enough money left to pay his passage home on a Slade ship. At "settling up time" each Fall the value of goods advanced to the planter and his employees on credit, during the season, was subtracted from the value of produce brought in. The difference was paid to the planter in cash or credited to his account. The price paid for fish was negotiated between the merchant and the planter. In later years it became law that the cash price of fish had to be set early in the season. The government introduced this law to counter abuses of the system by merchants; it had some effect but not a lot. A fisherman who complained to the authorities about the local merchant one year might be waiting a long time for credit the next year.

Another enterprise introduced by John Slade was the practise of sending vessels to fish on the Labrador coast during the summer months. They sailed out of their home ports in Newfoundland each spring, often taking the families of crewmen with them. Sometimes fish was salted on board ship, then washed and dried after returning home [ salt bulk fish]. Some schooner men set up rooms and cured their fish ashore in Labrador. Four hundred ships were taking part in the Labrador fishery by 1848. Slade owned many of these ships, others were owned by independent schooner men, often with Slade financing. The Labrador fishery reached its peak before nineteen hundred. The last schooners from Fogo went to the Labrador fishery in the nineteen - forties, a few were still making the trip from ports in Bonavista Bay and Notre Dame Bay until the nineteen - sixties. Slade also ran a number of vessels, mostly brigantines and brigs of about ninety to one hundred tons, on regular trading runs between Poole, Fogo, and Waterford, Ireland. His ships also traded to Spain and Portugal for salt and cork, and to Italy to trade fish for wine and fruit. Ships owned by Slade at the end of the eighteenth century were: Love and Unity, [Capt George Elford], Molly, Fame, Johannes, Delight, Juno, Sisters, [Capt. John Hayter], Nancy, [Capt. Thomas Northover], Hazard, [ Capt. Thomas Pollard], Stag, Amphitrite, Bulbury, [Capt. Thomas Frampton], this vessel sank in Eastern Tickle on August 15,1819, Perseverence, [Capt. John Dugdale], Otter, [Capt. Peter Samways]. Martha, [Capt Richard Bartlett],this ship was probably named for John Slade’s wife, Martha Hayter.

When John Slade died at Poole in 1792 he was a very rich man with no heirs, his only son John Hayter Slade having died at Fogo, of smallpox, in 1783 at the age of 28 years. When Slades will was probated at Poole in 1793 his assets were estimated at seventy thousand pounds. To put this in perspective, a captain on one of Slade’s ships at that time was making thirty-six pounds per year. He would have had to work for one thousand nine hundred, forty four years and five months to make this amount of money. Slade’s estate went to his five nephews John, Robert, Thomas and David Slade, and George Allen.

The nephews took over when the fishery was enjoying its most prosperous period. This period lasted from 1774 to about 1830. A lot of the prosperity was the result of wars being fought at the time. The period began with the American Colonies and their French allies fighting the British in the American Revolutionary War 1775 – 1783. Then the French were out of the business due to their own Revolution in 1789, and the Napoleonic wars 1796 – 1815 . From 1812 to 1815 the British and Americans were at war in North America. Throughout all this time the British Navy controlled the North Atlantic, a discouragement to New Englanders trading their fish in Europe and to the French fishing in Newfoundland. The Newfoundland merchant traders were left with no competition in the European fish market. Their only worry was the capture of their ships, and occasional raids on their Newfoundland ports by American and French privateers. To counteract this threat, they armed their vessels and persuaded the Government to provide protection for the ports. The Royal Navy had cannon mounted ashore at Fogo, and trained a small militia to protect the harbour. Some of the ships carrying Slade’s trade goods were granted Letters of Marque by His Majesty’s Government. Marmaduke Hart’s Exeter, armed with twenty four guns, was one of these privateers. The privateers could protect the unarmed cargo ships as well as bring in enemy ships as prizes of war.

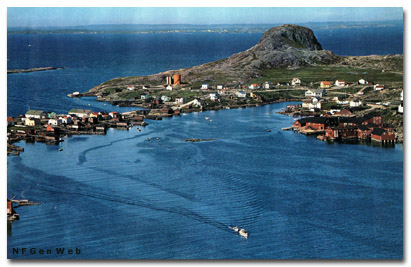

Fogo Harbour, Slade / Earle Premises

The Slades did not operate as one large family owned company, but rather they were a family of merchants who owned and operated several companies. They sometimes worked in partnership with each other and often in partnership with other merchants in Newfoundland and Labrador. All branches and associated companies traded with John Slade & Co. at Poole. At its height in the first half of the nineteenth century the Slade family had branches in Fogo, Tilting Harbour, Twillingate, Sop’s Arm. Nippers Harbour, Greenspond, Catalina, Elliston [Bird Island Cove], Trinity, Hant’s Harbour, New Harbour, Heart’s Content, Carbonear, St. Mary’s, and in Labrador, at Battle Harbour, Venison Islands, St. Leonard’s and St. Francis Harbour. After the death of John Slade Sr. nephew John Slade Jr. managed at Poole, Thomas Slade managed the Fogo branch. Robert managed at Twillingate.

In the late seventeen hundreds Jeremiah Coughlin owned the premises located on Wigwam Point in Fogo Harbour. He arrived around seventeen sixty-four and was apparently an agent for a group of Bristol merchants. He was also appointed Naval officer for the port and it was he who installed the cannon around the harbour in seventeen seventy-one as protection against American and French raiders. He also trained a local militia to defend the harbour. Coughlan is probably most famous or infamous, as the father of Pamela Simms. When Coughlan went bankrupt in seventeen eighty-two the firm went to Mr Thomas Street. In 1813 Thomas Slade and William Cox acquired the property from Thomas Street and named it Slade and Cox. This acquisition gave the Slades just about total monopoly on Fogo Island. They started another branch of Slade & Cox at Twillingate effectively gaining a family monopoly there. When Thomas died in 1816 He left his shares to his cousins William Cox and Robert Slade. Robert 1768 -1833, became manager at Fogo, David at Battle Harbour, Labrador.

After the death of Thomas Slade the Wigwam Point business was operated as William Cox and Co. It next went to William Waterman & Co. who operated it for Garlands of Poole, and then it went to Thomas Hodge. All of these owners were from Poole and most of them were related. In 1918 J. W. Hodge retired to Toronto and sold out to a group of St. John’s investors. The new group was called the Newfoundland & Labrador Export Co. Ernest Hyde was the local manager, succeeded by Stanley Layman. The company stayed in business until 1958. Arthur Gill was the manager in the final years.

John Slade Jr. of John Slade & Co., Poole, and of Robert and John Slade & Co. of Twillingate, died at Poole in1827. He had been head of the Company at Poole while Thomas, David and Robert managed the business in Newfoundland. Robert left the Fogo operation in 1804 and bought, or built an establishment at Trinity. From there he launched the Slade businesses in Bonavista, Trinity, Conception and St. Mary’s Bays. The Slades, based at Trinity, had branches in Catalina, Elliston, Hant’s Harbour, Heart’s Content, New Harbour, Carbonear, and St. Mary’s. When Robert Slade Sr. died in 1833 he left his share of the business to Robert Slade Jr. and James Slade.

His son, Robert Jr. 1796-1864 was a magistrate for Fogo District as well as being a merchant running the Fogo branch. Two of Robert Junior’s sons died young. Robert Standley died in 1846 at age twenty-eight, and John, member of the Newfoundland House of Assembly for Fogo District and manager at Twillingate, died in 1847 also at the age of twenty-eight. Robert Jr. died at Fogo in 1864, at age sixty-eight. He is buried in the St. Andrew’s Anglican Churchyard with his two sons.

The company lasted until 1862 under Slade family ownership. The Slades operated under a variety of names, depending on who they were in partnership with at the time. Some of these names were John Slade & Co., Slade & Cox, William Cox & Co., Slade Cox & Co. [Twillingate], Thomas & David Slade, [Labrador],Thomas Slade Sr. & Co., Robert Slade, Robert Slade & Sons, Slade & Kelson, and Robert Slade & Co. After 1862 branches were sold to different buyers and most of them remained in operation under new ownership until the mid twentieth century.

The companies had been dissolved two years before the death of Robert Slade Jr. They were in no apparent financial difficulty at the time of closing out. The early deaths of the sons might have been a factor in making the remaining owners decide to sell. Increased competition from the new breed of merchants based in St. John’s was also a factor. The Duder Company started in St. John’s in the eighteen thirties. They were already starting to move into Notre Dame Bay and had set up at Fogo by 1860 [Mair & Duder]. They bought the Twillingate property of Slade and Cox in the early eighteen seventies and by 1888 they owned more than one hundred and thirty ships engaged in fishing and trading. The 1864 Lovell’s directory lists nine merchants, large and small, doing business at Fogo. The competition had certainly changed from what it had been thirty years earlier. The Fogo branch of John Slade & Co. was bought by John W. Owen, Slade’s bookkeeper at Twillingate, he operated as John W. Owen Co. Henry Earle, another bookkeeper worked for Owen at Twillingate. He was later sent to manage the Fogo branch. He bought shares in the company and they renamed it Owen & Earle. Later Owen sold out to Earle and retired. It operated as Henry J. Earle until 1917 when sons Arthur, Fred and Harold [1884-1954] joined the business. It then became Earle Sons & Co. Harold Earle was manager of the company until his death in 1954, his son Brian was manager at Fogo until final close out in 1968.

Fogo Harbour, Bleak House

For the most part the Slades maintained their ties with Poole and remained in Newfoundland only when business required it. They left no descendants in Newfoundland. The four graves in the church yard, Bleak House, and the ruins of a couple of old buildings are all that remain of the Slades in Fogo.

Don Bennett

31/7/2001