|

The Odyssey of the FS240

Gordon Collins, the watch-keeper, poked his head through the wheelhouse window and peered into the night. A fierce winter storm was raging. Heavy snow blanketed the ship, while gale-force northeast winds howled around her. She rocked from side to side, riding the swells, as one massive wave after another broke over her bow, threatening to swamp her.

Gordon pulled back, just as a blast of icy spray washed over the deck and slammed against the window.

"Looks like we're in for a long night of it," he remarked to Bert Dominie, the helmsman.

"Couldn't agree more," Bert grimly replied, as he struggled to steer the course ordered by the captain.

It was just past midnight on Friday, February 13, 1948, off the east coast of Nova Scotia. For twenty-four long hours now, the former U.S. Army Supply vessel, the FS240, had been battling the storm, which still showed no signs of abating. Navigation was hazardous, and below-zero temperatures continued to wreak havoc by freezing the spray the high winds were hurling over the sides. All day it had been a constant struggle to clear the ice that had built up on the deck and the riggings--and everything else within contact. Hour after hour the crew had taken turns beating at it, with ice mallets and axes, to prevent it from becoming heavy enough to endanger the ship. They had worked constantly at keeping the scuppers free too. Unless the sea water pouring over the bow could run off the deck, it would turn to a slippery sheet of ice beneath them.

Now, only Gordon, Bert, and Arthur Sutherland, the chief engineer, remained on duty. The captain, at the point of exhaustion, had retired to his quarters, located directly off the wheelhouse, while the rest of the crew had gone to their cabins for a few hours' sleep. While Bert maintained a steady course, Gordon switched from one side of the wheelhouse to the other, checking on the ship and the storm in general. From time to time, the watch-keeper glanced at the clock, as the FS240 slowly inched forward.

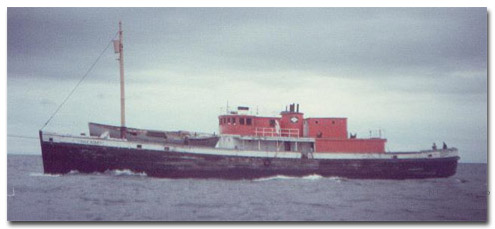

The FS240, soon to be renamed the Atlantic Charter II, was on her maiden voyage. She had recently been purchased from the American War Assets by the Collins brothers--Frank, Stanley, and Dorman--of Carmanville, Newfoundland. Constructed in San Francisco, California, during the last months of World War II, she had been used for two or three years to ferry troops on training exercises around the San Francisco Bay area. Until the Collins brothers bought her at an auction as war surplus, she had never sailed out under the San Francisco Bay bridge.

Two of the brothers, Frank and Dorman, had gathered a crew to meet the ship in San Francisco and to bring her home. Stanley had not accompanied them; he had stayed behind to attend to family business.

The captain was 41-year-old Frank Collins. Although he held only a mates coastwise certificate of competency, he was a seasoned mariner, long since accustomed to the deck of a ship. He'd come from a family of shipbuilders and seafarers, used to plying their trade along the rugged Newfoundland coast. His father, William, who had died less than a year before, had commanded a succession of family-owned ships and had taught his sons well. Adversity was no stranger to Frank. He'd faced dangerous situations before. Back in '29, while he was first mate on the Helen Vair under the command of his father, the schooner had been caught in a vicious hurricane and driven into the middle of the North Atlantic. They'd survived by their wits, and by the timely arrival of a Norwegian freighter, who rescued the captain and crew just before the Helen Vair sank beneath them.

For the most part, the crew were veterans too. On this trip, the ship's mate was Dorman Collins, the youngest of the brothers but, at 27, with a number of seafaring years behind him. Gordon and Bert were also at home on the sea, as were second engineer George Normore and the ship's cook, Eric Wicks. The only relative newcomers to the trade were 17-year-old Roy Collins, the son of the eldest Collins brother, Anslum--who had once been master of his own schooner, but who had died in 1937--and 17-year-old Duke Collins, Frank's son. A thirst for adventure had brought the boys onboard the FS240, but for Duke at least it was the start of a long career.

The FS240, a 540-ton, black oak construction freighter, was a good, sturdy ship, and the Collins brothers were proud of their purchase. She was a well-powered vessel, with an 875 horsepower Fairbanks Morse diesel engine and five-foot propeller blades. She was also equipped with two magnetic compasses and a tube radar set--the first radar set that had ever been on a ship owned by Newfoundlanders. Unfortunately, the tubes were subject to failure and the last of them had been used days before, rendering the radar inoperable. That she was now sailing without the aid of radar equipment was not a very enviable position to be in, given the wildness of the storm.

Roy Collins lay awake in his bunk, listening to the sound of the waves battering against the ship. Tired as he was, he couldn't sleep, and his mind focussed on the chain of events that had brought them here.

They'd left home in November 1947, flying from Gander, Newfoundland, to San Francisco in a circuitous route that had included stops in New York City, Chicago, Kansas City, Los Angeles, and Oakland. At first he and Duke had welcomed the air travel--you didn't get to do too much of that growing up in Carmanville--but at the end of the day they were glad to touch down in San Francisco.

They'd certainly had plenty of time to take in the sights. Upon their arrival, they'd discovered there were legal problems in getting the ship released from the U.S. government, and they'd spent the best part of two months billeted in a hotel, waiting for the lawyers to do their thing.

Finally, though, the problems had been solved and they were ready to leave. It was going to be a long voyage home, but he'd looked forward to it. City life was wearing thin, and he'd been anxious to taste the salt air again. Because they were going from San Francisco to Puerto de Balboa, and proceeding from there through the Panama Canal, the captain had known they would use up all the fuel the ship could carry. He'd ordered that extra be loaded on board and stored here and there--in pretty well everything but their boots. He'd also secured a load of canned fruit to be dropped off in Santiago, Cuba, to help offset some of the expense of the trip.

They'd cast off January 5, bound for the Panama Canal. This portion of the voyage would have normally taken about ten days but took almost twice as long as that.

The first week out had been fine. The powerful engine had pushed the ship at her top speed of 13 knots, and they had all enjoyed getting used to the feel of her slicing through the water. She'd looked good, too. The Americans had painted her a "battleship grey" , but they'd taken care of the dismal colour during their long wait in San Francisco by applying a new coat of black paint. It had certainly given her a more polished finish.

The smooth sailing had abruptly ended the second week, when they'd run into the remnants of a hurricane. For several days they'd had to face the wind dead on and had not been able to make much headway. Although they had eventually managed to outride the storm, there had been a cost. Life rafts had been lost overboard, and several windows in the wheelhouse had been smashed by the waves. They'd had to do makeshift repairs, mostly with the plywood that was stored on the ship, but at least they'd been in a position to make those much-needed repairs. Even more lamentable, most of the brand-new black paint had been erased by the waves and the FS240 now sported again her battleship grey.

Just as the ship had entered Puerto de Balboa, her engines had stopped. In spite of the extra fuel they'd loaded on board, her tanks were dry. The two weeks' voyage from San Francisco and the tussle with the hurricane had depleted their stores and it was only by God's grace that they'd made it to shore.

They'd dropped anchor and prepared to launch a lifeboat to go ashore. But the lifeboat, which had never been used since it had been installed, had been difficult to lower. Uncle Frank had had to climb into it and try to get the balky mechanism to function, while the crew fiddled with the ropes. Eventually, though, their efforts had paid off and the life boat had been lowered to the water.

Roy winced as he thought of what had happened next. Just as Uncle Frank was trying to release the boat falls by hand, he, Roy, in his eagerness to use the automatic release mechanism, had prematurely pulled the release lever. Uncle Frank had been unable to get his thumb out of the way before it had gotten caught in the apparatus. What a string of oaths had ensued! Not that he could blame the poor fellow--the captain's thumb had been mangled and he'd been crazed with pain. It must have seemed to him to have taken forever to row the few miles to the pier and locate the doctor who'd attended to his thumb.

Once that mishap had been dealt with, they'd had to make arrangements with the Port Authority to tow the ship to the pier for refueling. Only then had they been ready to make the one-day journey through the Panama Canal.

It was January 20 before the FS2240 had finally pushed her bow into the Atlantic Ocean and headed for Santiago, Cuba.

They'd sailed into Santiago harbour on January 22, after having experienced some difficulty with the engine during their last hours at sea. While the canned fruit was being unloaded, the engineer had investigated the trouble. The problem itself hadn't been that bad. A cylinder head was leaking, but while they would have no problem fixing it, they'd had no tools to do the job. There had been nothing to do but make the rounds ashore and on every ship they could find to see whether they could borrow the tools for the necessary repairs. The tools had been harder to find than they'd figured. A full week had passed before they'd had any luck. Luck had come to them when the cargo-passenger ship, the Canadian Constructor, had sailed into the harbour. As luck would also have it, the Constructor's captain was a fellow Newfoundlander. His engineers had lost no time in boarding the FS240 and had made the repairs within hours.

That Newfoundland captain had certainly helped them out of a difficult situation. By the time he'd arrived, they'd all been going stir crazy. The captain in particular had been climbing the walls, impatient to be off again, so they'd immediately cast off their lines and once again headed for open sea.

The next stop had been Inagua, a 12-hour trip from Santiago. There, they'd loaded coarse salt, destined for sale in Fortune for the Newfoundland cod fishery. He himself had been fascinated by the making of the salt. It was produced by pumping seawater into huge lagoons; the hot Caribbean sun then worked its magic and evaporated the water, leaving only the salt, which was then scraped up and placed into bags. The newly made salt--and the FS240--was now headed for Belleoram, in Placentia Bay.

By rights, they should be arriving in Belleoram and clearing customs a day from now, on February 14. But with the storm raging overhead, they'd be lucky to make it at all. Roy pushed the worrisome thought aside. If he'd ever had faith in anyone, it was in the captain and crew of the FS240.

He closed his eyes and turned his thoughts to more pleasant matters...the young maid who was waiting for him at home.

Up in the dimly lit wheelhouse, Gordon Collins continued his vigilant watch. For hours now, the vessel had been running by dead reckoning. Still, they were confident in their course and that Belleoram was not much more than a day's voyage away.

At 3 a.m. the door to the captain's quarters opened. Frank stepped into the wheelhouse, hitching his braces over his shoulders and rubbing the sleep from his eyes. Still partly in a daze, he slowly made his way to Bert Dominie's side, just as Gordon retreated from the wheelhouse window. Over the steady throb of the engine, Gordon calmly said: "Bert, for the past few minutes we've been steaming through small pieces of ice, about the size of dinner plates."

An oath sailed through the air. Before it could land, Frank sprang to the telegraph and frantically rang "Full astern!", while bellowing to all and sundry: "We're ashore! We're ashore!"

His deep-rooted instincts had instantly told him that for the ship to be steaming through small pieces of ice, the ice had to be coming from a nearby shore, where the wind and the waves had beaten it up by smashing it against the land or some rocks.

When the FS240 had been in port in Santiago and the big engine had been shut down, the power to operate the ship's electrical system had been provided by one of two diesel generating plants in the engine room. Once the ship was under way again and cruising speed had been reached, the engineer had switched over to a different generator, which ran off a pulley system connected to the main drive shaft. This is the generator that was engaged when Arthur Sutherland, in the engine room with oil can and rags in hand, received the "full astern" signal from the bridge. He knew that an emergency situation had to have developed for the captain to have ordered the ship from "full ahead" to "full astern" without any warning and that in all likelihood they were in danger of running into another ship or aground. Without hesitation, he threw the lever, which shut down the Fairbanks Morse engine. Then, using the compressed air ignition system, he started the big engine in reverse. This action knocked out the generator, plunging the ship into darkness. Every light, even the running lights, went out.

The FS240 shuddered and shook at the huge propeller fought for purchase in the dark waters below. The momentum of the heavily loaded ship inexorably kept her going forward while the propeller laboured to stop her headlong plunge.

On the bridge, the captain swung from one side of the wheelhouse to the other, desperately trying to see into the night. He ordered the watch-keeper to the deck to lower the sounding lead so that they could determine how much water was under the ship's keel. The first report showed that less than eleven feet of water was underneath the ship. And although the FS240 had slowed, it was still moving forward. Gordon's voice could be heard above the din: "Nine feet...eight feet...six feet...". Still the ship moved forward, with the engine going flat out and the propeller clawing into the frigid waters.

By now, everyone on the bridge was fully aware of the danger the ship was in. Any minute, they were expecting to hear the sickening crunch of the ship running aground. But just as they had steeled themselves for what seemed to be the inevitable, the FS240 came to a stop.

Only four and a half feet of water was under the keel when the engine and the propeller took over and gradually backed the ship away from disaster. With each report of increasing depth, Frank Collins' tension eased. But it was not until deep water was reached that he felt it draining away.

Along the way to the open sea, the running lights, and a modicum of safety, was restored. The captain ordered the ship to steam slowly to the southeast and, once safe water safe gained, to "heave to" with her bow pointed into the wind. This they did and waited out the long night.

When daylight broke, the snow was still falling, thick and fast, and visibility was still nothing. It was not until noon that the skies began to clear and the storm finally ended.

Reaching for his sextant, Frank took a sight. They were forty miles west of their intended track. They were, in fact, just off the southeastern coast of Nova Scotia. Sable Island winked ominously in the distance.

Frank emitted a low whistle, as an image of the danger they'd faced flashed through his mind.

Then he turned to his crew and grinned. "Come on, me sons," he said, "Let' s go home."

* * * * * * *

Sable Island is notorious among mariners in this part of the world as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic", having claimed numerous ships and sailors over the centuries. Only a combination of favourable circumstances and the instincts of a real sea dog prevented the FS240 that night from being the latest of a long list of ships to meet disaster on this rugged island in the North Atlantic.

|