|

FOREWORD

The title "From Helvick Head to

Hescut Point" may require a word of explanation. Helvick Head is the southern

point of Dungarvin Bay in County Waterford, Ireland. Most of our settlers

have been traced to the four or five counties surrounding it. Hescut Point

is the lighthouse point in Shoal Cove, St. Brendan's largest settlement.

Its proper name is Haircut Point but I have chosen to spell it as the islanders

pronounced the word. The two names were chosen to represent the ancestral

search of the St. Brendan's Irish for a new home. This booklet is an attempt

to capture at least part of their history. Constraints of time and money

forced us to do a less than thorough history. Some elements have been explored

briefly, others not at all. It is quite possible that there are errors

and omissions, that we hope to remedy at some later point. It's like Uncle

Tom Walsh's song: you might find a three leg but we'll mend it bye and

bye.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A community history is never the

effort of one person but a product of the collective memory. A big thank

you to all of the people who talked with us about the past and contributed

their old photographs. I am especially grateful to my brother Bill, who

did most of the legwork, and the various other relatives who were drafted

from time to time. The late Uncle Pad Casey, who remembered six generations

of some families' history and took the time to teach it to curious young

people, was a major contributor. John Whalen, one of the island's older

living residents was similarly helpful. Help from relatives and neighbours

is expected at a time like this but two men whom I had not known previously

took the time to sort through years of their own research notes to provide

me with information. A special thank you to: Dr. John Mannion of the MUN

Geography Department and Tom Beresford of Corner Brook.

I would also like to express my

appreciation to:

-

Dan Croke, Father Shea, and Dan Broderick

for their slide collections

-

The staff of the Provincial Archives

-

The staff of Maritime History

-

Captain Stone

-

Father Mike Hynes

-

Charlie Falk for the cover photos

-

The Departments of Education &

Municipal Affairs

-

The Post Office

-

Archdiosce Archives

-

Ron Kelly, Gerry Newhook and Bruce

Sparkes

-

for the advertising

-

Mrs Nell Hennessey and Mrs Nell Bridgeman

-

Drs MacPhearson and Hancock at MUN

Geography

-

My husband and family, who put up with

my absences

-

Margie, at Quikprint, who put up with

all of us.

MISTS OF TIME

The largest island in central Bonavista

Bay was called Cotterell's in the earliest records. As a child, I embraced

the romantic notion, expressed by Archbishop Howley, that it was a corruption

of the name Corte Real, after the famous Portuguese navigator. However

examination of the records and consultation with the experts failed to

produce any evidence to back the theory. It seems much more likely that

the name, which is a surname of both England and Ireland derive from the

name of one of the fishing captains who used the area in the heyday of

the migratory fishing fleet. Bonavista Bay was used by the English fishermen

from the 1600's and a large wooded island with several harbors would not

have been overlooked. Cotterell had been shortened to Cottle's by the time

most of our ancestors arrived. I am not implying that the English were

the first to use it. The French were also active in the Bay and the tales

of Frenchmen buried on Connors' Point might have some credence. It would

also be a mistake to assume that the first users were white. Recent excavations

at The Beaches have uncovered a Maritime Archaic Indian site with the possibility

of other cultures, perhaps the Beothic. Indian graves in Shoal Cove have

long been a part of our folklore.

I approached this work expecting

to find that settlement had occurred earlier than the mid 1800's which

most family tradition had suggested. After all, the area had permanent

settlers going back to the 1700's. Greenspond, Gooseberry Islands, Fair

Island, Barrow Harbour and Flat Island all supported growing populations

years before. The largest and most hospitable of the islands could not

have been ignored. After a year of study I am forced to conclude that permanent

settlement was indeed delayed. However, I believe I have found the answer

and it does, in part, support my own belief that the early settlers of

the Bay could not afford to waste such an island. Land on Cottle's was

being used by the Gooseberry Islanders for farming, firewood, hoop making

and timber.

There is plenty of evidence of Gooseberry

Island use of the land. The geologist Jukes, writing in 1840, tells of

a Gooseberry Island farmer who made a living entirely from the land. Gooseberry

Island production far exceeded the capability of its available soil. Charlie's

Back Cove, Hayward's Cove and Daley's Cove bear the names of Gooseberry

Islanders. While we have no evidence that Hayward actually lived there,

we know that Tim Daley wintered in Daley's Cove, presumably to be closer

to a good supply of wood. Charlie Burry certainly lived in Shoal Cove and

at least six families held land on the island. Many of Cottle's first settlers

lived on Gooseberry Island and other islands first; indeed some continued

to live there well into the 1870's. Three English Protestant families lived

in Shoal Cove long after the arrival of the Irish immigrants.

The mass settling of the three outside

coves (Hayward's, Dog and Shoal) in a relatively short period at mid century

seemed to have resulted from a collective decision on the part of the Irish

Catholic element, who had been shifting around Bonavista Bay, to make a

community for themselves. They were already a community in the religious

sense - intermarrying, sponsoring at each other's weddings and christenings.

This group had been restlessly moving since their arrival from Ireland

a generation or two previously. They had families who would benefit from

the institutions of church and school. A community would make such things

possible and the large island seemed to offer an appropriate setting.

Two factors about these people probably

contributed to the next and final name change of the island. They were

descendants of Irish immigrants who held tenaciously to their Catholic

faith but for the most part had been converted from farming to a seafaring

life by necessity, in the Newfoundland of the last century. The first priest

sent to shepard this strange flock was mindful of both aspects of their

lives when he decided that Cottle's island was no longer appropriate as

a name for their community. He chose, instead, the name of St. Brendan's,

the legendary Irish Bishop and patron saint of navigators. In the 6th century,

Brendan set out in search of the "isles of the blessed" believed to lie

beyond the western ocean. He journeyed for months in a boat made of oxhide

stretched over oak ribs. Whether he reached Newfoundland is debatable but

Tim Severin's voyage in 1976 proved that it was possible. In fact, 'The

Brendan'reached land just 30 miles from the island and true to our seafaring

heritage a St Brendan's man was on the John Cabot when she went out to

offer assistance. We don't know how close Brendan himself came but his

"pillars of crystal" suggest that he got close enough to encounter the

ice field that has been plaguing his namesake every spring since. It is

worth considering at this point that it is some indication of the priest's

position at the time that he didn't bother to inform anyone in authority

of the name change. Official maps and charts record the island as Cottle's

Island to this day. To officially change the name would take a formal petition

and a lot of red tape so no one has ever bothered. For the benefit of any

non-native reading this: St Brendan's, on most maps, appears as a synomyn

for Shoal Cove.

This booklet will trace the history

of the island, which though the last to be settled, is the only isolated

settlement remaining in Bonavista Bay. It will attempt to present a picture

of the origins of the first settlers, their work, their social lives, their

education, their interaction with the world, and the role of the Church

in their lives. It will trace the ups and downs of population and the evolution

of social institutions and government services. The role of its women and

the importance of the schooner fleet will be examined; the latter in somewhat

general terms since it is the subject of another work, in progress at the

moment by one of our captains. Since all of these will overlap in time,

it is difficult to operate chronologically. The various sections will weave

backwards and forwards in time.

EARLY SETTLEMENT

There is no doubt that the earliest

settlers on Cotterells were English Protestants. Three families resided

in Shoal's Cove and were joined for a brief period by a fourth. The first

recorded birth was in 1849 in Church of England records. Suzanna of Charles

and Ann Burry was baptized on Nov 15. Edward Vater (of Dorset, England)

and wife Susan had five children on the island and an early daughter Caroline

had a child there herself in 1869. The Burry's had another child in 1856

and a second Burry family appear briefly in 1853 with the birth of Thomas

to Jacob and Mary Burry. Ben and Sarah Saunders had three children in Shoal

Cove between 1865 and 1871. John and Susan Golden had a child baptized

in 1869. It is possible that Susan is the 20 year old Burry girl. This

child was baptized by Ben Saunders, so one can assume that its health was

precarious enough to make waiting for the Greenspond minister risky. Interestingly

enough, when Ann Vater married Nathaniel Goulding of Hay Cove in 1877 she

is still recorded as being from Shoals Cove. In the fifties, Burry and

Vater acquired land grants to their property, along with Ben Parsons who

had two. Ben Saunders did not register his land. At least one Irish Catholic

worked with this group. Martin Berrigan, a cooper, sponsored some of their

children as well as many of the children of the Irish group that moved

in the fifties. He does not appear to have wife or children of his own

and it can be speculated that he was employed by Vater and Burry in what

was probably a cooperage business over on the point. The only reminder

of this group lies in the name "Charlie's Back Cove" and the expression

"you Vater" to someone who has made a mess of some enterprise.

The mid century mark saw a centralization

along religious lines occur within Bonavista Bay. Within 12 years (1845-1857)

the scattered pockets of Irish Catholics had started to congregate. In

this time 107 Catholics moved from Greenspond, Pinchard's Island, Black

Island, Barrow Harbour and Gooseberry Island's and 128 Catholics appear

on Cottle's Island. That is not to suggest a complete transfer because

Gooseberry Island retained 43 Catholics with the continued presence of

the large Hynes family, the Beresfords, Cashins and some of the Dooleys.

Some Catholics were already entrenched on Burnt Island and, for the most

part, remained there. Nevertheless, it is possible to imagine that some

collective decision was taken to move in and occupy the large island that

was functioning as a farm and woodlot for prosperous Gooseberry Islanders.

Whether this decision was influenced by the attending clergy is unclear.

Certainly, such corralling of the flock would make the Shepard's job so

much easier as well as allow the development of Catholic schools, a goal

since 1832. Perhaps it was simply the desire of a group, who had been rootless

since leaving Ireland a generation or two earlier, to find themselves a

home of their own. The almost simultaneous arrival of over 100 Irish Catholics

on Cottle's in the early 1850's was to change its history forever. The

specifics of who, when and from where will be dealt with a little later

as I pursue each family.

The take over was not without incident.

The English settlers had the best of both worlds - easy fishing access

from Gooseberry Island and spacious farmland in Cottle's. I suspect that

the movement to permanent living arrangements for the families already

discussed and the securing of early land grants was an attempt to stave

off the Irish invasion. Two events in the 50's speak of the tension of

the times. The "goat war" of Shoals Cove, which involved an actual landing

of Gooseberry Islanders intending to put down the goats that presumably

were destroying their crops. This incident, which is supposed to have involved

guns, could have become very ugly indeed. Pad Bridgeman is credited with

having averted trouble with the time honoured tactic of "the best defence".

The second event may well have been in retaliation for the first and was

foolhardy to say the least. It consisted of an act of extreme provocation

on the part of the Irish Catholics. It seems that on July 12 when the Orangemen

were holding their annual parade on honour of King Billy, the Irish decided

to hold their own. It is not known if the Irish living on Gooseberry Island

took part, but a group from Cottle's brandishing the Harp and Shamrock

went in boat to Gooseberry Islands and paraded through the community daring

their neighbours to stop them. That the two incidents ended without bloodshed

and a minority group survived on both islands for the next 20 years, suggests

that neither group took the rivalry too seriously.

The original settlement involved

only the 3 outside coves, Hayward's, Shoals and Dog. All 19th century records

use Dog; the change to Dock appears to have been made in this century.

Shalloway Cove was not settled until the 1870's, although some of the families

were related to the first settlers. Anyone looking for records might be

surprised to find ancestors listed as Hayward's Cove , who in fact have

never lived there. This is because the original settlement was often called

Hayward's Cove, Cottle's Island. I assume this resulted from the fact that

the original parish property, cemetery, school, post office and government

wharf was all located in Hayward's. Many of the earliest settlers lived

in Dog Cove; the first birth recorded on the island to a Catholic family

occurred in Dog Cove in 1850. The Aylwards, Connors, Smiths, Broomfields

were all in the first wave of settlement. The Caseys, Daniel Brawders and

two Turner families settled in Hayward's. The White's, Mackeys, John Walsh,

John Dooley and Bridgemans squeezed into Shoal's Cove along with the existing

English families. By 1857 Dog Cove had 42 people, all Newfoundland born

and all R.C. Hayward's Cove had 37, two born in Ireland, all R.C. Shoal's

Cove reported 60, 1 born in England, 2 in Ireland, 11 Church of England,

49 Catholic.

I have traced the founding families

as far as time and the accuracy of the early records allowed. There are

several problems that make it impossible to be absolutely certain on some

people. One is the murkiness that exists in the records prior to 1820.

There were periods when a priest was unavailable or did not reach to all

areas. Dean Cleary writes of mass baptisms, of marriages and baptisms performed

by ships captains, clerks, or anyone literate. Many early ceremonies were

performed by Protestant clergy either by necessity or to conform to rules

that required all such ceremonies to be recorded by the Established Church,

regardless of the persuasion of the participants. Since marriage certificates

did not contain names of parents and so many families used the same first

names, it is sometimes difficult to sort people out among their numerous

brothers and cousins. Sometimes a researcher has to make a good guess,

based on age, sponsors and proximity of other family members. The absence

of early death certificates, the habit of using the name of a dead child

for a subsequent birth, and the number of second marriages all add to the

problem of positive identification of people in the distant past. I will

present the known information on the founding families and in some cases

speculate on possible connections. The only order of presentation is by

coves. The families remaining on Gooseberry Island will also be done since

all of them contributed wives to the original settlers, even though their

own resettlement was later and roughly corresponds in time to the Shalloway

Cove settling.

CASEY: The Caseys were traders

from Cloyne, Co. Cork, with a room in King's Cove in the early years of

the nineteenth century. William died in 1815 at King's Cove. There was

obviously a full family here since several girls married in the twenties:

Mary to Maurice Devine of Co. Cork (1820) and Betsy to James Connors (1828).

Those girls are established as sisters to Michael, Bill and Tim because

of the presence of the boys at the weddings. William married Mary Power

in 1826, Michael Casey married Mary Meagher in 1831 and Tim remained single.

After selling the room in King's Cove to a man named Rey, the three Casey

brothers appear in several places before settling on Black Island in the

1840's. Several of their children were born there and they left it to move

to Cottle's in the 50's. There is some indication that the Caseys may have

lived briefly in Dog Cove since there was a Casey's Beach there. That they

were early in the settlement period is obvious from their location in the

best sheltered part of Hayward's Cove.

BRODERICK: All of the early

records present this name in its Gaelic form of Brawders as the early settlers

and the Irish speaking priests would have pronounced it. Daniel is a bit

of a mystery, appearing in the 1840's around Greenspond and Gooseberry

Islands. Family tradition had him coming from Youghal but a thorough search

has failed to substantiate it. Hayward's Cove held only two people who

were born in Ireland and it is fairly certain that they were his wife Elizabeth

and her sister Mary Anne (wife of Pad Turner). The most likely scenario

is that he was connected with William Brawders from Youghal who married

Anastasia Kennedy of Greenspond in 1826. Since Daniel married Elizabeth

Beresford in 1843, he is obviously not a product of that marriage but he

might have been a child from a previous marriage. Daniel, William and two

other Brodericks (Tom and Michael) appear in Greenspond during the 40's.

In 1843 Daniel married Elizabeth Beresford and settled on Gooseberry Island,

where the first of his children were born. He moved to Cottle's in the

first wave of settlement occupying the current family property in Hayward's

Cove, between two pieces of Casey land.

TURNER: It was a popularly

held belief that the Turners must have been converts to Catholicism because

all other Turners in the Bay are Protestant. I have found no evidence to

suggest that this was so. An Irish Turner was buried in Trinity in 1815,

indicating the presence of a Catholic group quite early. The Church of

England minister officiating makes it clear he is not interring one of

his own flock but doing the decent thing in the absence of Catholic clergy.

The St. Brendan's Turners all derive from the union of John Turner and

Johanna Ryan. Their marriage is recorded in King's Cove R.C. records in

1815 with the notation that they had previously lived together. There is

no mention of conversion either in his case or that of his sister Rebecca

who married James Norris in 1822. The Mary Turner who married Jeffrey Kean

of Waterford in 1803 may well be another sister and there was no mention

of conversion in her case either. John and Johanna had five sons: John

(1816), Bill (baptized in 1821 but born before the marriage), Abe (1819),

Tom (1824) and Patrick. Bill, who married Honora Fitzgerald in 1836 and

Pad who married Mary Beresford in 1841, were original settlers in Hayward's

Cove in the 1850's. The other three remained in Keels until the Shalloway

Cove settlement in the 1870's and which time they also moved to Cottle's.

All of these families were established before moving: Abe married Margaret

Burns in 1842, John & Sarah Walsh in 1843, Tom & Ellen Fennel in

1850. Several girls, who were probably sisters also married in the King's

Cove - Keels area: Rebecca & James McCormick, Catherine & John

Walsh 1844, Joanna & Nick Kelly, 1840's.

CONNORS: This is an example

of a family which is difficult to sort out because of too much information

rather than too little. It seems that two families , one from Wexford and

one from Waterford, contributed to Bonavista Bay's population in the early

1800's. To further complicate the issue, both families had Timothy as a

commonly used name. I have concluded that the Waterford branch is the one

which produced our line of Connors though a case could be made for the

Wexford group. The Waterford branch intermarried with the Caseys (through

the marriage of James to Betsy Casey) and the name Tim seems to have entered

the Casey family for the first time soon after. Tim Connors married Kitty

Rey (presumably the daughter of the man who bought the King's Cove room

from Caseys). Our original settler Tim appears to have been born in 1829

to Jim and Betsy. He married Bridget Aylward and moved to Cottle's in the

50's. William Connors who appears at the same time is either a brother

or a cousin.

AYLWARDS: This family has

the distinction of being among the first settlers in the bay and on the

island. The problem with that, of course, is that by the 1850's they have

grown to such numbers that sorting them out is not easy especially when

so many have the same first names. They probably all descend from the original

James who had a plantation in Keels in 1772. He moved to King's Cove before

1800 and is said to be the first settler there. In 1805 James and William

Alyward shared a room in King's Cove and James had a room in Open Hole

(now Openhall). He also claimed Bullock's room in Keels. Those two are

probably sons of the original James since the rooms were claimed by inheritance.

A James Alyward, planter, died in King's Cove in 1832 leaving a widow Hannah

and ten children. His oldest son, also called James, was most likely the

man who married Kitty Gready in 1828. Given the number of children in that

family and the possibility of Bill also having a similar number, it is

easy to see where confusion can occur. Some of these families remained

on the south side of the bay and the King's Cove records do not always

indicate place of residence. You are forced to make judgements based on

the names of the people with whom a group is associating to determine where

they are at a given point in time. I will attempt to deal with the five

males who were on this side of Bonavista Bay in settlement period. Three

marry and settle in Greenspond: Jim (married to a Rogers) and John and

Pad (both married to women named Lush). I have not attempted to trace those

three beyond Greenspond: many of the Catholics there moved to the St. John's

area, perhaps they did as well. Two moved to Cottle's in the early days

of settlement: Mike, who married Margaret Walsh in 1850, was probably the

Mike born to James and Kitty Gready in 1828. Bill is harder to pin down

because King's Cove records show a Bill marrying Catherine Barker in 1830

and a Bill marrying Margaret Murphy in 1836. In addition two Bridgets marry

early Cottle's settlers: Pad Bridgeman and Tim Connors. Obviously two branches

of the family were feeding into the island and it is difficult to say with

certainty whether Bill and Mike were brothers or cousins.

BROOMFIELD: Stephen Broomfield

was baptized an adult in 1844. This could be a conversion but the records

do not say so and adult baptisms were not uncommon in the days when services

of the clergy were irregular. He married Martha Smith and moved to Cottle's

in the 1950's. The origin of this name is not certain. Some suspect it

to be a corruption of the English Bloomfield but an Ann Brumfield married

in St. John's in early 1800's to a Wexford man was apparently Catholic

and using the name as it was pronounced on St. Brendan's.

SMITH: John Smith from County

Tipperary was present in Greenspond in the 1820's. Two brothers, probably

sons of the original settlers, Bill and John marry in Greenspond in the

late twenties and thirties. John married Johanna Kennedy and Bill married

Mary Bryan of the Youghal Bryan family who were planters in Greenspond.

It is unclear if the two men moved into Cottle's with the first wave of

settlers. They both certainly appear in the records as sponsors to children

of their relatives but John is not shown as having children himself here.

Quite possibly his children are already born before the migration since

he married in 1828. Certainly Smith females, daughters and perhaps a sister,

figure prominently in early settlement. In fact, the first two children

born to Irish settlers on Cottle's are born to Smiths: Ellen of William

Smith and Mary Bryan, and Margaret of Martha Smith and Stephen Broomfield.

Margaret Smith was married to early settler Sam Brown and Suzanna to Michael

White. A Catherine Smith was married to Michael Kelly on Burnt Island in

the same time period. It is difficult to say for certain that all of these

wives were from the same Smith family because a group of County Cork Smiths

were also living across the bay. Given the amount of interaction with Greenspond

and Gooseberry Islands (where some of the marriages took place) it is fair

to assume that most were.

BROWN: Original settler Sam

Brown, who married Margaret Smith in 1846, was most probably the son of

the Michael Brown on Gooseberry Islands in 1825 since the witnesses at

the wedding were John Brown and Emilia Hynes. Whether Michael was descendant

of William Browne of Poole (agent for MacBraire and later a merchant himself)

or connected with the Wexford Browns, who were in King's Cove as early

as 1815, is difficult to tell. Certainly there does not appear to be any

evidence to suggest that the Cottle's Brown was converted to Catholicism.

BRIDGEMAN: This family proved

to be the easiest one to trace because of their limited numbers in Newfoundland.

Pad Bridgeman married Patience White in King's Cove in 1822. His son Pad

was born in 1825 and married Bridget Aylward in 1843. Two other Bridgeman's

appear briefly in the records in the early period: Mary and Peter. We have

no information on them. There were Protestant Bridgeman's from Devon in

St. John's prior to this but the Bonavista Bay group appear to have been

Irish Catholics. Patrick moved to Cottle's in the fifties, apparently accompanied

by his father who is said to be buried on the Shoal's Cove Broderick's

land. Though Bridgeman appears as a sponsor on Black Island we have no

proof that he lived there. Perhaps he was carrying the priest around the

Bay in his boat. All St. Brendan's Bridgeman's are descendants of this

line.

WHELAN: Like the Turners,

the Whelan name figures in two different settlement periods. The Black

Island Whelan's: James and wife Mary White moved to Cottle's with their

fellow Black Islanders, the Caseys. John Whelan, who married Margaret Cashin

in 1854 on Gooseberry Island remained there until the 1870's when the family

built a fishing room on Cottle's and moved up. Another John Whelan married

a Batterton and lived in Greenspond. Relationships, if any, within those

three groups are unclear. Confusion is heightened by the fact that the

name sometimes appears as Phelan.

MACKEY: Thomas Mackey of

Faha, City of Waterford was married in 1803 to Martha Richard (Pichard)

and became a planter at Bonavista. His son Thomas married Susan Oldford

of Salvage in 1829 in the famous rowing elopement. Thomas was living in

Bonavista at the time, though he may have been working up in the bay. I'm

doubtful about the elopement story because several of her relatives are

with them at the wedding. He must have had a big punt if he rowed them

all across the bay. Thomas and Susan (who is mistakenly called Ailworth

in at least one record entry) moved to Cottle's in the early fifties along

with their son John, who married Ellen Beresford in 1855. The Edward who

married Bridget White in 1858 was probably another son. John and Susan

had some of their last children on Cottle's despite their 1829 marriage.

WHITE: Four adult males appear

on Cottle's in the fifties as well as several females who marry original

settlers. It is unclear if all are from the one family or if there are

cousins involved. Some of these appear to have been on Gooseberry Islands

at first. Joseph was married to Mary Long and Sam to Mary Elliot prior

to settling on Cottle's. Thomas married Suzanna Mackey in 1856 and Michael

married Suzanna Smith in 1865. This family may have descended from the

Bonavista planters William and Edward White of the 1830's. There is also

the possibility that they derive from the 5 sons of twenties lighthouse

keeper Jeremiah White of Wexford. With a name so common and murky records

it is difficult to pinpoint this family accurately.

WALSH: This man is not to

be confused with the Shalloway Cove settlers, although he may have been

related to them. Shoal's Cove John Walsh married Mary Anne White in 1856

and went to live in the vicinity of the current power house. I believe

he is the John Walsh who was on Gooseberry Island and had a child with

Ann Hynes in 1850. He seems to have moved to Cottle's with the Whites.

There are so many John Walshs in the KCRC registry that it is difficult

to say for certain whose son he was. There were several Wexford Walshs

married in King's Cove in the twenties and at least one branch from another

county.

DOOLEY: The Dooleys lived

on Gooseberry Island in the forties and James remained there until the

final resettling of the Catholic element. John married Catherine Beresford

in the 1850's and moved to Cottle's. Since his later children were born

on Gooseberry Island, I assume that he returned to the family property

for some reason. Catherine, a sister, married Pad Beresford and continued

to live on Gooseberry Island until the Beresford family moved. James Dooley

moved to Cottle's when he left Gooseberry Islands. This family came originally

from Plate Cove.

FAMILIES REMAINING ON GOOSEBERRY

ISLAND

BERESFORD: This family, though

not a founding family of Cottle's via the male line, played a tremendous

part in the early settlement as can be seen from the number of wives provided

to founders. It is also one of the few families to be traced precisely

to their origins. Philip Beresford and Johanna Rielly emigrated from Dungarvin,

County Waterford around 1830 with several children. Their daughter Catherine

is reported to have been born at sea: son Patrick was born in St. John's

in 1832. The Book of the Beresfords gives Mary Ann (Pat Turner) as born

in 1823 but her headstone suggests 1819. The obituary of Elizabeth (Daniel

Broderick) has her 78 when she died in 1901, which would make her birth

in 1823 in Dungarvin. Bridget, who married William Crotty of St. John's

in 1856, was also supposed to have been born in Dungarvin. It is not certain

if Ellen who married John Mackey in 1855 was born in Newfoundland or Ireland.

The remaining children were born in Newfoundland: Thomas in 1834 (married

Sarah Blackmore and Catherine Miles): Anastasia in 1840 (married Holwell).

For some particular reason, the Beresfords are sometimes referred to as

Blackmores in parish records. Even the married girls who have been called

Beresford in earlier records mysteriously become Blackmores in later ones.

I don't know if it's possible that the Beresfords, who had bought Black's

room on Gooseberry Islands had assumed the name for business purposes.

That would hardly account for Elizabeth Broderick appearing as Blackmore

in parish records. Philip Beresford did not live to see the settlement

of Cottle's. He died in 1843 from exposure after swimming to catch a drifting

boat while cutting wood on a nearby island several weeks earlier. Johanna

and the boys remained on Gooseberry Island until the 70's movement into

Cottle's.

CASHIN: This is another family

who contributed to Cottle's settlement through the males of the line made

only a brief appearance here in later years. Richard Cashin (wife Mary

Fennell) was in Bonavista Bay as early as 1813. In 1822, in debt to MacBraire,

King's Cove, he offered his property for sale and took his effects, including

a skiff, to Gooseberry islands where he planned to reside. (Bonavista Court

Records) This couple raised a large family on Gooseberry Islands. Richard,

Michael, Patrick and Peter Cashin held land on Gooseberry Island by the

90's. When the Gooseberry Island Catholics moved Richard lived briefly

in Hayward's Cove before moving to Gambo with the others. Cashin females

remained as wives of William Hynes (Joanna), John Whelan (Margaret) and

Henry Turner (Elizabeth).

HYNES: James Hynes married

Betsy Noonan prior to 1825 but this may have been a second marriage for

him since a James Hynes had married Rebecca Bryan in 1815. The Noonans

were on Gooseberry Island, the Bryans in Greenspond. Their children were:

Edmond 1825 (married Emma Pond), William, also baptized in 1825, Sarah,

1829 (married a Cashin), Ann (married John Mesh in 1850), John, 1849. Tom

who married Catherine Hartery in 1855 may have been an early son or a nephew.

If the Ann who had a child with John Walsh is not the same one who married

John Mesh in 1850 there was probably a second Hynes family in the area.

Several Hynes females married the Cashin men of the 70's and remained on

Gooseberry Island until near the end of the eighties. The Hynes men began

to move to Cottle's by the early 80's.

CROKE: The Cottle's Crokes

descend from Michael (1847-1911) and Ellen Mesh. This is an unusual name

in Newfoundland and I suspect Michael is connected to James (married Johanna

Dwyer of Fogo, 1823) and Richard (1803, St. John's). Both were from County

Wexford. The Croke's lived on Gooseberry Island until the end of the eighties

when they moved to Penny's Cove. In 1923 they moved to Shoal's Cove to

their current properties.

MESH: John Mesh was baptized

an adult in 1844 and married Ann Hynes in 1850. This probably represents

a conversion as other Meshs occur in Protestant registries in the bay.

He remained on Gooseberry Island until the last group moved to Cottle's

at the end of the 80's. A brother, James, also lived on Gooseberry and

a sister married on Burnt Island.

COTTLE'S GROWTH

Meanwhile the Cottle's community was

increasing steadily as the grown sons who had arrived with early settlers

started families of their own and as they were joined by other migrants.

The Hogans arrived in mid sixties with two girls marrying into Dog Cove

and Edward marrying Bill Turner's daughter Ann and moving on to Turner

land at the bottom of Hayward's Cove. Edward was the son of Tom Hogan and

Elizabeth Long (born 1837). The Dwyers arrived from Burnt Island and remained

until the deaths of Paddy and Mary in the twentieth century. The family

of John Miles and Bridget Coleman were present in the early years but then

disappear from the records. John Miles who marries Margaret Broomfield

in the eighties may have been a son of the original settlers.

The Rielly's were added to Shoal's

Cove in the seventies with the marriage of Catherine White and Tom Rielly

who had appeared in Gooseberry Island records in the 60's. There were Riellys

across the bay in the 20's and 30's, (Philip and Daniel appearing as sponsors).

Phil Beresford's wife was of that name and she appeared to be accompanied

by a brother since a Rielly sponsored their first Newfoundland born child,

Patrick in St. John's in 1832. The only other possibility of a connection

lies in a marriage that occurred in Battle Harbour in 1832 between Tom

Rielly and Catherine Whelan. Since both names occur later on Gooseberry

Island it is possible that this marriage produced our Tom. Shoal's Cove

Irish population increased with the marriages of the second generation

of settler children. The emigration of the English group freed more land

and several Hayward's Cove families, Brodericks and Turners moved into

Shoal's Cove as their numbers increased. The name Lane was added with the

arrival of school teacher Edward Lane (wife Catherine Ducey). Another Lane

from the south side of the bay, Bill married a Hynes and lived over on

the point for a while. The Kellys completed the Shoals Cove settlement

with the arrival of Frank (wife Martha Miles). Frank was born in 1886 to

Maurice Kelly and Bridget MacDonald. Maurice was probably the Maurice born

to John Kelly and Elizabeth Connors in 1863 but since there were so many

Kellys around Greenspond, Pinchards Island and Burnt Island in the early

1800's it is difficult to be certain.

Two new family names were added

to Dog Cove in the 1880's with the marriage of John Samson to Suzanna Broomfield

in 1880 and the birth of John Colbert to George and Martha Broomfield in

1883. Samson probably came from Flat Island and Colbert from Conception

Bay. In the early twentieth century, Tom Devine married Ann Aylward and

settled here. Donovan and Mason would complete the names of Dock Cove later

in this century with the marriages of two men from Trinity bay to Aylward

and Devine girls.

Hayward's Cove picked up one additional

name: Rose, through the marriage of David to Mary Turner. This family lived

at the extreme upper edge near Ron Turner's property today. George Paul

completed the names of Hayward's Cove with his marriage to Elizabeth Turner

in the twentieth century. There were several children born to island girls

and outside husbands who may have worked here for a while but the families

did not stay. The remaining name to be added to the original community

was Fennel and since that was related to the Shalloway Cove settlement

it will be dealt with in the next section.

SHALLOWAY COVE SETTLEMENT

The prettiest and most sheltered part

of Cottle's had gone unsettled for over 20 years. Perhaps it was because

of the distance from the fishing grounds in a time of oars and sail. It

is hard to believe that it wasn't used to shelter boats as it has been

for a century afterwards. Certainly its name suggests that it may well

have been used as early as the migratory fishing fleet days for a shalloway

referred to a type of a boat used to move supplies between Greenspond and

the planter stations in the bay. There is a story that people on the other

side of the island did not know that settlers had arrived in Shalloway

Cove until a woman walked out of the woods up in Shoal's Cove. I find this

a little hard to believe since the three Turner men who were early settlers

in Shalloway had two brothers living in Hayward's Cove and operating schooners.

It's a safe bet that the families would have communicated their intentions

and the existing settlers would probably have assisted in the move. The

Shalloway Cove families were, mainly, established families on the south

side of Banavista Bay who were being caught in the land and berth squeeze

that occurred as families multiplied rapidly. Most were mature men with

early children grown to near adulthood. The families were related to one

another by blood or marriage. They were linked to early settlers on both

Gooseberry Islands and Cottle's via their sisters and aunts. Fennel females,

for instance, had figured in settlement since the first Mary came to Gooseberry

Island with Richard Cashin. While it is relatively easy to trace the families

to the other side of the bay, the common nature of the surnames and first

names of this group makes it difficult to sort them among their cousins

on the other side.

FURLONG: The St. Brendan's

Furlong's derive from Martin (born 1839 & Bridget Fennel. He was the

son of Patrick Furlong and Margaret Heany (married 1836). I have not been

able to establish for certain the parentage of Patrick. I suspect that

he is a brother to James and John (children of John & Mary Ryan) who

were baptized in Trinity in 1825 but not infants at the time. I suspect

that Patrick may be an older brother who had been baptized earlier to the

south. Both James and John had children named Patrick, indicating that

the name was in the family.

RYAN: This was a prominent

name in King's Cove - Keels area for some years. The Irish merchant family

had extensive property and many ships in King's Cove, Trinity and Bonavista.

Because of the number of families with the name it is difficult to be certain

of relationships. Shalloway Cove's original settlers were brothers Pad

(wife Mary Fennel) and William (wife Johanna Fitzgerald). They appear to

be sons of William (wife Mary Martin). Many of their children were born

in Keels, including Pad's daughter Elizabeth who taught school in Shalloway

Cove in 1892. An earlier Miss Ryan, who taught in the Haywards Cove school

may have been a relative as well.

BYRNE: The Byrne's are supposed

to be from Thomastown, County Kilkenny. Whether it is a respelling of the

earlier name Burns (as in Abe Turner's wife Margaret) or a totally different

name is unclear from the records since different priests seem to use the

two interchangeably. Brian Byrne (wife Johanna Walsh) was one of the early

settlers in Shalloway. He was married in 1880 on Cottle's. Johanna was

the daughter of the founding Walsh family who were early settlers in Shalloway

Cove.

WALSH: This early Shalloway

Cove family appears to have arrived at the same time as the Shalloway Cove

Turners. Dr. Mannion's research indicated that Johanna Ryan, who had been

married to John Turner and produced the Turner children, had remarried

Robert Walsh after Turner's death. I was inclined to doubt the connection

to our Walshs until I found that Johanna Walsh was buried beside two Turners

in our graveyard. This would seem to indicate that John Walsh (wife Margaret

Fennell) was the son born to Robert and Johanna in the 1830's. This would

make him step brother to the Turner men of Hayward's and Shalloway Coves.

The location of the Walsh and Turner properties in Shalloway Cove would

seem to suggest a connection between the families.

FENNELL: This family, remembered

as Shoal's Cove residents in later years, were originally in Shalloway

Cove. The Fennell family was widespread on the south side of Bonavista

Bay from the early 1800's. They were involved in the fish and shipping

trades and had premises in Newman's Cove. John, Tom and Patrick Fennell

all came to Shalloway Cove. John moved to Gambo and Patrick married Mary

Larkin in St. John's in 1893. A number of females were involved in the

island's settlement as well: Bridget (Martin Furlong), Mary (Pad Ryan),

Margaret (John Walsh), Ellen (Tom Turner in 1850) another Ellen (Mick Aylward

in the 70's). Though several of the girls were sisters, the generation

gap suggests that at least two were aunts of the later group. There are

four Fennell families as early as the twenties: it is difficult to accurately

pinpoint all children since so many names are repeated. The four probably

all relate to the original Richard in Newman's Cove. My best guess is that

most of ours derive from the Plate Cove family of Thomas and Ellen Walsh

but John and Elizabeth, who have children in the forties are also possible.

Obviously the Turner and Walsh wives are more likely to be sisters than

daughters. Mary Fennell, who married Richard Cashin in 1822, was probably

a daughter of the first Fennell. The Fennells moved to Shoal's Cove with

Tom's marriage to Johanna Hynes. They were involved in business, ran a

schooner, operated the post and telegraph offices and for a while kept

a "public house" or liquor establishment.

The final additions to Shalloway

Cove came with three marriages to Turner females. Mike Hennessey married

Abe Turner's daughter Bridget: Tom Knox and John Kean married Tom Turner's

daughters Johanna and Ellen. Knox and Hennessey were winter men from around

the St. John's area. It is possible that Knox was connected with the Tom

Knox from England who married Johanna Maddox in King's Cove in 1849. John

Kean was from the Burnt Island Kean family. Penney's Cove, where the current

ferry wharf and fish plant is located, may have been used by the Pennys

in presettlement days but was settled in the twentieth century by Fitzgeralds

from Keels. These Fitzgeralds had contributed wives to each wave of St.

Brendan's settlement. Bernard, Edward, Patrick and Henry Fitzgerald all

lived in Penny's Cove but the families have all died out or moved away.

Henry and his wife moved down to Ryans after the death of their son. Penny's

Cove, empty for years, is now enjoying a resurrection with the building

of a hotel to join the fishing and transportation businesses established

there in recent years.

SCHOONERS

Nothing, beyond their religion and

Irish origins, characterizes St. Brendan's people more than their love

affair with schooners. From their earliest days they built, owned, mastered

and sailed in schooners. John Turner's 50 ton "Mary Anne" is the earliest

one of which we have record (1863). In a 60 year period, 1875-1935, the

Newfoundland Ships Registry records some 60 vessels, ranging from 17 to

60 tons. This list only includes ships built or owned on St. Brendan's.

Another whole category, ships built and owned elsewhere but mastered by

St. Brendan's men, was missing from that calculation. In 1911 with a population

of slightly over 500, St. Brendan's had 22 schooners. This was an increase

of 14 from the 1901 figure of 8. Obviously with that many schooners, virtually

all of the population was involved in the usage in some way. Even with

the employment of hardy boys and girls, schooner owners would have to look

for some crew from outside the community. Undoubtably some potential marriage

partners entered the community via a berth on one of these schooners.

Why so many schooners in such a

small area? Part of the answer lies in the direction of the Newfoundland

fishery at the time. As the population grew on the old English shore it

was becoming more and more difficult to acquire fishing berths and waterfront

property for everyone to pursue a land based fishery. Depending on the

fish to come to a particular spot placed the landsman in a risky position

in bad years and already the Newfoundland cod fishery was experiencing

bad years. The schooner solved two problems, allowing the fishermen to

go after the codfish in the relatively underutilized northern waters and

relieving the overcrowding in eastern bays. By the time St. Brendan's was

settled, Bonavista Bay was being very widely fished by the people of the

communities which had been founded so much earlier. There really was not

a lot of fishing ground available to those new settlers.

The Newfoundland schooner fleet

was growing rapidly as locally constructed vessels replaced the English

migratory fishing fleet. The development of the seal fishery and the creation

of a local supply industry, as Newfoundland's population expanded to include

hundreds of small communities far removed from the Avalon, both provided

other sources of income for schooners apart from their primary fishing

role. A schooner was expensive to build and maintain. It simply was not

feasible to own one for fishing alone. However, if there were ways to make

money from March to December, then a move to schooner ownership was a natural

progression for an ambitious man who might have been a successful shore

planter a century before. The group who came to St. Brendan's were resourceful

family men with sons and brothers to provide the labour and heavily wooded

Bonavista Bay at their backs to provide the raw materials. Is it any surprise

that they would seize upon the trend of the times and set about the building

and sailing of schooners? A schooner man's job was a full time one. With

a break of a few weeks around Christmas time, you belonged to the schooner

the rest of the year. Winter involved woods work either to produce freights

of firewood or railway ties to be carried to St. John's and sold in the

spring or timber for building and repair. Spring meant that painting and

outfitting the vessels had to be done and fishing gear placed in readiness.

In the early days schooners were also used for sealing before the Newfoundland

Seal Hunt became dominated by large steamers. A dangerous venture it must

have been in those little wooden sailing ships and some years ice conditions

were such that few of them could get far. Nevertheless, they tried and

under good conditions got an early start on the year's wages with a successful

hunt. King's Cove merchant James Ryan wrote in his diary in 1890 that he

was outfitting Bridgeman of St. Brendan's for the seal hunt and we can

assume that the other schooner men of the island would have been doing

the same.

When navigation opened in the spring,

the schooners would make one or more trips to St. John's to bring in supplies

and bring out the fruits of the island's winter labours in the woods. There

might be several shorter jaunts to King's Cove, Greenspond or Bonavista

since many of the vessels were owned or supplied by merchants in those

ports. Then it was off to the northern fishery on the French Shore or the

Labrador. This voyage was heavily dependent on ice conditions to the north.

When all conditions were good and a schooner managed to get early passage

and good fishing, it was possible to make a second labrador voyage. If

you made it home before the end of July then a second voyage was feasible.

Many times though it took the summer to use all your salt and get home

with your fish in time for drying. Some years the return was so late that

the schooners had to go across to Nova Scotia to ship fish, having missed

the last large boat shipments. The Kean Brothers is shown in a mainland

newspaper high and dry in the Bay of Fundy after just such a venture. Normally

though a schooner's fish was shipped to the outfitting merchant at his

premises and the crew then went about collecting fish from the landsmen

on the east and northeast coast and delivering this catch to the merchant

for a fee. Following the fish collection, the remainder of the fall was

spent in carrying any available freight around the bays. By December frozen

harbors and storms tended to put an end to the sailing season. Some schooner

men found jobs with the larger vessels which carried the fish to Spain

or the West Indies. At least two St. Brendan's sailors met their deaths

on those voyages: Mike Bridgeman and Walter Hynes. Bridgeman is remembered

for having appeared to Fr. Badcock for Communion on the night of the storm

which took his life. His brothers, who survived the storm , were on another

ship, suggesting that this overseas passage was a relatively common occurrence

at the time. Regardless of whether their sailing was on local or foreign

ships, getting home for Christmas at the end of their sailing year was

the goal of schooner men.

Though the work was hard and often

dangerous the life of a schooner man was more varied and interesting than

that of many of their more stationary descendants. They had a mobility

that many nine to fivers must envy. They met new people all the time and

visited and socialized with friends and relatives all down the shore. At

my husband's home in Brent's Cove, the porch was built by the Furlong cousins

of his grandmother. Stormbound in one of the nearby ports, they walked

miles through the woods, helped with the construction and in good St. Brendan's

fashion stayed to christen the new structure with a square dance afterwards.

Such casual dropping in on friends and relatives of the larger Irish community

and indeed with fishing buddies from all places along the way was characteristic

of their lifestyle and certainly served as a break from the confining nature

of shipboard life. Young men often found sweethearts and some wives on

those voyages. Perhaps one of the reasons that St. Brendan's never seemed

to be afflicted with the inbreeding that was characteristic of so many

small communities was that the mobility of our schooner men gave them plenty

of opportunity to seek wives elsewhere and new bloodlines regularly joined

the community. I don't mean to imply that only the men were involved in

the schooner life. The female role in this lifestyle will be examined in

another section. It has long been accepted that the sea exacts a price

for the livelihood it provides. Sometimes the price is the destruction

of the vessels themselves and our history is all too full of wrecked and

burned ships. The Tinker Bight photo is graphic evidence of what the fury

of a North Atlantic storm could do to a harbor full of sailing ships. Fire

onboard was every sailor's nightmare: there was so little that could be

done. One of my earliest memories is my father's nonchalant explanation

that he had returned early from a trip in the bay because his bunk was

burned but there were also tears that night for the gallant A.W. Bridgeman,

that he had left in flames at Lakeman's Island. Sadly, it was not ships

alone that the gods of the sea claimed as ransom. There are men, boys and

girls on the list and many names have been lost in the mists of memory.

-

Mike Bridgeman (1890's on a voyage

from Spain)

-

Walter Hynes (turn of the century,

overseas voyage)

-

Kate Connors (lost in a shipwreck,

Grey Islands)

-

Mike Hennessey (1898 Greenland disaster)

-

Tom Hogan (1921 drowned at Indian Hr.)

-

Gertrude Turner, 16 (1924 from burns

on schooner)

-

Bernard Furlong (1924 in hospital at

St. Anthony)

-

John Walsh, 11 (1929 on Labrador, unknown

causes)

-

Mike Bridgeman (1933 collision Silver

City/Ethel Collet

-

Martin Furlong (1935 drowned at Gros

Water Bay)

-

Martina Furlong, 18 (drowned on the

Labrador 1944)

-

Captain Jim Croke (died on the Labrador)

-

Ernest Keel (knocked overboard by main

boom)

What was the fate of schooners in general?

I guess, like all things they went full circle. They probably brought us

to this island (literally), gave us a reason to remain, grew with us and

coloured our perception of who and what we were and having served their

purpose passed into history. The growth of their numbers parallelled the

population growth in the early years but by the time our population peaked

in the 1960's the schooners and their way of life was already dying. Though

they had the modern progression from sails to engines, they could not compete

with roads and trucks of the post Confederation era. Perhaps their last

heyday was in the closing years of World War II when 13 Labrador schooners

were based at St. Brendan's. By the 50's the number had shrunk to 3. Centralization

of hundreds of isolated communities and roads put through to hundreds of

others sounded the death knell of the schooner. There was no longer cargo

enough to be transported by sea. The individual schooners ended their days

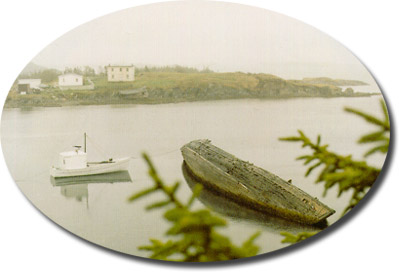

in various ways. Some like the one in our cover died as had many sisters

before in beaches and harbors as food for sea creatures, others like The

National Convention saw new life as converted yachts and at least one was

sold abroad and lost at sea before she reached her destination. a few,

though not ours, became museum pieces and tourist carriers. They were a

proud and vibrant part of our past and our identity is forever entwined

with them. The photo pages which follow is our salute to their era. The

sailor Brendan was indeed an appropriate patron for the ships and crews.

ANECDOTES

The following is a sampling of the

many stories from our past. Some of the details may have been lost or changed

in the retellings and my own memory may be faulty on others. Like most

of our stories they involve spirits, schooners and humour.

THE HAUNTING OF THE ISLAND BELLE

Shortly after the Broomfields acquired

this schooner from their merchant, they began to hear strange stories about

her. It seems a man had been killed by falling from her rigging and the

vessel was supposed to be haunted. No other crew could be found to take

her. Undaunted, they set off for their Labrador voyage but soon learned

that the stories were true. Daytime was relatively uneventful but no one

could sleep a wink at night. Hatch covers would lift and fall, stove lids

hurl themselves in the air and cooking gear appear to take wing. Morning

would find a serene ship, with no sign of damage or intrusion. The poltergeist

phenomena continued unabated until the frazzled crew reached Battle Harbor

and refused to go further. The skipper knew he would have to do something

to save the voyage. It happened that Bishop March was on his summer visit

to the Labrador and word reached Captain Broomfield of the presence of

the man of God in Battle Harbor. Approaching such an exalted person was

not to his liking but he saw himself with little choice. The Bishop willingly

came onboard, sent the crew below and engaged in some sort of exorcism.

There was great altercation between cleric and spirit, most of it heard

but not understood by the men. The spirit seemed unwilling to leave but

depart he finally did. The Bishop blessed the ship and crew and sent them

on their way. While this solved the problem for the St. Brendan's men,

it seems to have created a new one for the stationers at Battle harbor.

The spirit is reported to have terrorized the harbor for the rest of the

summer. I guess a further exorcism must have been required the following

year.

CARROLL'S DOG

For this story I am indebted to

P.K. Devine's "Old King's Cove" and I retell it for its St. Brendan's connection.

The latter part of the last century saw a lot of exploration for minerals

in Bonavista Bay. Since many of the islands are remains of extinct volcanos,

the possibility of valuable deposits of gold and other mineral could not

be overlooked. Carroll, who no doubt left us Carl's Mine on Pitt Sound

Island, was over in the bay on a schooner prospecting. Since both he and

his right hand man Ned Martin had relatives on St. Brendan's he stopped

a while to visit and was much taken with a new pup that someone had. He

bargained to buy the pup on his return and went on to his job. Carroll,

a quick tempered man, charged his crew that he would fire any man who overlooked

a single piece of white quartz. The exploration took more time than he

had figured and the time passed when he should have been back to buy his

dog. Not wanting to leave his promising site, he dispatched Ned Martin

to St Brendan's to get the pup. Ned got down to the island, went on the

spree with the crowd and it was several days before he sobered up and remembered

his mission. He found that Carroll's pup had been sold to someone else

and the only one remaining of the litter was an ugly little mutt with one

black side to his face and one white one. Fearing his master's temper,

he thought it unwise to return both late and unsuccessful, so he took the

pup. Carroll, who was as superstitious as he was short tempered, was enraged

when he saw the dog. "It's the devil you've brought me" he roared, fearing

for the success of his mining venture. "But sir, you told us not to overlook

any piece of white quartz", said Martin, sheepishly, "I thought that's

what the white on his face might be".

THE LAKEMAN"S ISLAND GHOSTS

A family of MacDonald, presumably

from the Melrose area, lived for some time at Chalky Head. Late one winter,

tragedy befell the family when their house burned, killing the parents

and several children. The kindly Protestant who reached the scene after

the fire undertook to take the bodies to a Catholic community for burial.

Ice conditions prevented them from reaching St. Brendan's and they were

forced to inter the remains on Lakeman's Island, without benefit of proper

burial services. Some time later, a schooner from St. Brendan's carrying

the priest on his regular rounds to visit the other Catholics in the bay,

harbored for the night at Lakeman's Island. It seems that all hell broke

loose almost immediately. Hideous shrieks and lamentations filled the air

and the crew were terrified. Eventually someone remembered the graves and

decided that the priest was the object of the spirits' unrest. The priest

was rowed ashore in the dead of night and left alone, at his own request,

to perform the burial service. Afterwards, he signalled for a boat to take

him back and a peaceful night followed now that the spirits had been properly

laid to rest.

FOLLOW BROOMFIELD

Captain Fennell had just returned

from an extremely bad voyage to the Labrador. To add insult to injury he

was forced to unload at the merchant's premises directly behind Skipper

John Broomfield who had a bumper load. As if the shame was not hard enough

to bear, the merchant had the bad taste to comment "You should have followed

Broomfield". Captain Fennell nursed the insult all winter and when spring

came decided to get his revenge. As his schooner was being provisioned

for the Labrador, Fennell entered the merchant's office and laid his compass

on the desk.

"What do you want me to

do with your compass, Skipper? Is it broken?" asked the surprised merchant.

"I don't need it" said Fennel.

"Don't need it! How are you going

to get to the Labrador without a compass?"

"I'm going to follow Broomfield",

replied Fennell.

KEAN'S MYSTERIOUS ADVENTURE

A schooner skippered by John Kean,

voyaging to the Labrador shortly after World War II, had a strange adventure

that does not appear to be credited to spirits. Crossing the Straits on

a fine night, the schooner was abruptly jolted with such force that a trap

skiff being towed behind came onto the deck and crashed into another stowed

on deck. The vessel and gear received enough damage to force them to return

to St. Anthony for repairs. There was no evidence of collision; no other

ship travelling that night encountered difficulty; and there were no submerged

rocks. The only possible explanation , beyond a supernatural one, is that

the vessel encountered an unexploded mine left over from the war years.

RUSTY JOE AND THE FRENCHMEN

I'm not sure if the Aylward in this

story was a resident of St. Brendan's or one of their relatives who stayed

across the bay but I include it since he is obviously one of the models

used by Fr. Fitzgerald in the creation of his composite character Demon

Dan. It seems that, in 1883 Aylward in command of the Comet and several

schooners from King's Cove were fishing at Quirpon on the French shore.

Seeking to improve their luck, they moved on to Cape Onion. There they

encountered a Frenchman, who considered himself "captain of the room" and

he ordered them to stop fishing. The rest complied, although they were

legally entitled to fish. Aylward refused to stop and the Frenchman cut

their lines and confiscated sails and oars from all schooners . Aylward

struck the Frenchman several hard blows with a gaff and was set upon by

a large group of French. Despite the uneven odds, he managed to escape.

After a day or two sails were returned to the other schooners but Aylward's

were held until the arrival of a French man-of-war. The sails were then

ordered returned and the Comet was allowed to leave the area.

TO MAKE A LIVING

The earliest residents fished with

handlines from their boats. In 1857 they produced 1240 quintals of cured

cod fish and 2.5 tons of cod oil. They also used seal nets to catch seals.

As we have already seen, they rapidly progressed to the building of schooners

and acquired the mobility to chase fish to other parts and to travel to

the ice floes to pursue seals. There was some use of seines and cod nets

in the early years but after Whitely's invention of the cod trap it was

widely accepted as the best way to catch cod in large quantities. Traps

and trap skiffs were used at home and on the schooners. At least one family,

the Walshs, were involved in the bank fishery for a period of time. By

1890 lobsters were making up 10% of the exports from Newfoundland and most

outports, including St. Brendan's, had several canning factories. The fishery,

even when it was good, could not provide for full time livelihood. Farming

was an essential part of our settlers lives from the start. In the very

early years, with a small population, the island produced 900 barrels of

potatoes and supported over 150 farm animals. There is some evidence to

suggest that St. Brendan's exported farm produce to the other islands of

Bonavista Bay. The cutting of firewood and timber, for sale to Conception

Bay and the St. John's area, was also a means of acquiring some hard cash

for the purchase of necessities. Hoop making for the fish trade seems to

have been a part of the island's auxiliary employment since its founding.

The cutting of railway ties was also common well into this century. Naturally,

not all of the work involved cash value. The residents were busy improving

their properties: clearing land, building fences & adding new homes

for sons and daughters. They also built, with free labour, the schools

and churches which served the community in those days.

Three factors around the turn of

the century changed the work patterns of island residents: steamers, the

railway and paper mills. Together they provided the option of seasonal

migration for wage work. Some of these migrations involved whole families

going into the Bay for woods work but the greater number involved the men

only. The woods work took them as far west as Lomond but most of the early

work was in Indian Bay and the central Newfoundland area. The steamships

took many to the ice floes but many more embarked farther afield to work

in Sydney and the Boston States or up the St. Lawrence to Montreal. Of

course, not all who travelled that distance returned but they are the subject

of another section. Many longtime residents of the island had work stints

away from home for varying periods of time before returning to home and

family. It was to become a feature of St. Brendan's life that continues

to the present. Though it placed a tremendous burden on those left behind,

particularly the wives, it was seen as the only way to maintain a decent

lifestyle. Later in this century the mines, the American bases and the

development of Labrador towns all provided the same opportunity for men,

who though fishermen by trade, had made themselves competent enough in

construction to take advantage of the work.

The fishery itself remained for

St. Brendan's largely a Labrador fishery. Most of this was done in our

many schooners, each of which provided for 5-8 men and a girl. However,

many families had an early history of working as stationers on the Labrador.

They would be freighted down in schooners or steamers, fish from their

summer stations and return in the fall. Most of the island's crews of the

20's and thirties worked Battle Harbor - Snug Harbor stations. With the

demise of the schooner fishing fleet and years of failing fishery at home,

the early 60's saw a return to this system with as many as eight crews

working in the Domino - Spotted Islands - Griffins Harbor area. It was

a measure of the changing emphasis on education that several of the crew

would join their families only after the Public Exams had been written.

Their fathers and grandfathers had regularly missed 2 or 3 months of school

to accommodate the fishery in the past.

The home fishery was changing as

well. It had expanded to include more species but bad years and outside

employment had reduced the numbers involved. The 60's brought the introduction

of a new type of vessel: the long liner. Unfortunately, the first two (the

Joan and Annie Byrne and the Blue Flier) came at a period in which the

fishery was in decline and both were subsequently sold. The smaller vessels

which succeeded them have met with a little more success and the addition

of the caplin, crab and flounder fishery has provided the owners with more

options. Meanwhile, there has been a revival of the regular shore fishery

and at least 50 men and women are now involved in the industry. The building

of a holding plant in 1977 gave all fishermen the opportunity to ship their

catch fresh, removing the inconvenience of waiting months to ship salt

bulk fish. The decision to extend UIC benefits to fishermen made the last

few decades a little easier but it is still an enterprise that is filled

with uncertainty. The present problems with fish stocks add to the worries

of the men and women involved but there is always the hope that the fish

will return as they have done after all the bad years in the past.

The present provides more nonfishery

jobs than earlier years. Employment is provided by the ferry, the fish

plant, the schools, shops, community projects and the power plant. Some

residents have always been employed in sea going jobs which allow them

to return to the island when they are off shift. There is still a lot of

seasonal migration when jobs are available in the construction trades and

most young people will try at least one mainland expedition as did their

fathers and grandfathers before them. Like most other Newfoundlanders,

the people of St. Brendan's hope for a time when their sons and daughters

will be able to stay at home if they choose.

A WOMAN'S PLACE

My students of Newfoundland Culture

have a perception of the role of women in the past that is one of abject

drudgery. They see women as oppressed by men, overworked and confined to

their little coves and harbors. Though the hard work cannot be disputed,

the picture is not a very accurate one. Actually the women of our past

had far more status and mobility than those of us who grew up in the 1950's

would suspect. Remember they were part of a schooner culture with the males

absent from the community for substantial periods of time. Women had full

responsibility for houses, gardens, children, and animals. In many ways,

they were efficient managers of large family properties. For example, Aunt

Peggy Walsh not only raised a family and delivered babies; she supervised

a large fishing operation and even travelled to the Grand Banks on the

family's banker. The one thing that stands out when you examine records

is their mobility. The number of excellent professional photos of the islands

girls and women suggest that they made regular trips on the schooners.

With the coming of steamers, many travelled away to work, sometimes as

far as the Boston States. Even the earliest women appear to have travelled

around the bay, appearing as spomsors at christenings and weddings, after

they were settled with children on Cottle's. Juke's as early as 1840 speaks

of giving rides to females travelling between the islands.

I've always assumed that a female

marrying outside her community a century ago would have said goodbye to

her family forever. Imagine my surprise to learn that my own grandmother,

Martina Walsh of Fleur de Lys, had gone home to her mother to have her

second child as casually as a St. Brendan's girl today might join a relative

in St. John's or Gander. Her husband was going fishing on the Labrador

so he simply dropped her and her firstborn off on the way down and returned

to pick up his increased family in the fall. Similarly, Bessie Ryan who

was married in the White Bay was regularly visited by her brothers and

cousins and sent her teenage daughter up for a summer to visit the relatives

on St. Brendan's. If such mobility was routine in my own family's past,

I can only assume that it was common practice in other families as well.

In later years, girls from the island, working away from home in service,

speak of catching rides to Fair or Burnt Island and getting home with the

first relative or friend to pass that way. Of course, almost all families

allowed their older girls to work on the schooners of their fathers, brothers

and neighbours. As the schooners congregated in Labrador harbors, there

were many opportunities to mingle with boys and girls from other communities.

Many lifelong friendships and a few romances blossomed from these voyages.

Girls raised in the staid, confining atmosphere of the 1950's often envied

their grandmothers and aunts.

It is not my intention to minimalize

the hard work or the dangers of the lifestyle of the early women. I have

shown that some paid the same price as the men for the privilege of being

a part of schooner life. I don't believe it was a very easy task to cook

and clean on a schooner rolling in a North Atlantic gale. There couldn't

have been much privacy for a girl who had to work in such close quarters

with 5 or 6 men. Many of our older females are eligible for Veteran's Pensions

today because they worked in the submarine infested waters of the Straits

of Belle Isle during World War II. Schooner life was not exactly a cruise

on the Love Boat.

And what of those who stayed at

home? Their lives were filled as well. They had children, lots of them,

with the help of neighbours and midwives. Medical assistance was rare and

most of our people were brought into this world by women like Anastasia

Mackey, Rebecca Bridgeman, Ellen Walsh, Peggy Walsh, Bridge Aylward, Jose

Hynes and Lizzie Furlong. When things went wrong, many babies and some

mothers died. Perhaps the saddest part of examining the records is finding

that most families lost children, either in childbirth or from early childhood

diseases. Looking at ten deaths from meningitis in as many years, it's

easy to imagine the anguish of mothers who had to sit helplessly beside

those dying children. But life had to go on. There were gardens to be sown